The functional style part 9 - Pragmatism

Richard Wild

8 May 2019

•

11 min read

In this series we’ve taken a whirlwind tour through the topics related to functional programming that I think are most important to know, plus some extra that I think are good to know. We started with the basics, defining what I believe to be the essence of FP, and showed how programming without reassignment is actually feasible by using recursion and how tail call elimination makes it as efficient simple iteration. We covered first-class functions, lambda expressions and closures, map, reduce, and filter. We looked at higher-order functions, function composition and monads, currying, lazy evaluation, and concluded with a look at persistent data structures.

The functional style is declarative.

What I hope to have achieved, above all, is to convince you that the functional style is something that can be applied to most languages - and therefore is most likely applicable to your daily programming - and that it can save you time and effort if you do. The reason is that the functional style of programming is declarative. The functional style allows us to program more in terms of the outcomes we want, whereas the imperative style forces us to spell out in painstaking detail exactly how to get there. Let’s say we want to filter a collection of items by some predicate and sum what is left. In the imperative style, we have to iterate the collection, test each item with the predicate, and accumulate it if the predicate returns true. The purpose of the code can easily be lost in the details of how to achieve it. In the functional style, we can write pretty much in words what we want to achieve, without spelling out how it is to be done.

This isn’t even a new idea. You may well have been using a declarative data processing language known as the Structured Query Language for years already. This language allows the programmer to select fields from named repositories of data, where the data meets certain specified predicates. You may optionally order by certain data fields, or group by certain data fields in order to sum or count the data, and you may include or exclude groups of data having certain properties. You don’t have to programmatically navigate through the records, following links, searching for the data you want and collating it yourself, like programmers used to do with databases built on the old CODASYL model. The similarities between SQL and the collection operations made possible by first-order functions described in parts 3 and 4 are clear. Indeed the designers of the C# language went one step further and gave it an SQL-like syntax called Language Integrated Query (LINQ).

Functional vs. object-oriented programming.

Functional programming is seen as the new big thing, and some people have the mistaken belief that FP is a successor to object-oriented programming and somehow replaces it. I have seen many blog posts and articles proclaiming that “OO is dead.” I don’t think so myself. I see OO and functional programming as orthogonal and complementary, not opposed to each other. Clearly, OO programming cannot objectively lose any of its qualities in absolute terms, so the only way it would become obsolete is if something else came along that offers the same benefits, and better. Nowhere in this series of articles have we seen anything that does that.

Some people have the idea that object-oriented and functional programming are polar opposites or somehow mutually exclusive. Possibly, they have come to think this because first-class functions offer an alternative means of creating abstractions to the object-oriented approach of interfaces and abstract classes. It is certainly true that in Clojure I depend on classes and interfaces far less than I do in Java. But as we saw in part 3, the use of first-class functions to enable abstraction is not new. Nevertheless, the idea that functional programming makes OO programming obsolete is simply ignorant. In my opinion, this betrays a lack of understanding of what OO is all about. The real purpose of OO is to provide a convenient and disciplined way of achieving dynamic dispatch - runtime polymorphism in other words - without having to resort to function pointers. Viewed this way, there is no contradiction between OO and FP; both styles can be used in the same code, and I think it is good to do so.

After all, nothing about OO mandates that you must mutate state. Certainly languages like Java and C# make mutable state so natural that doing so is usually the path of least resistance: but that is not the same thing. It seems quite conceivable to me to have a language that allows you to couple data and functions together as OO languages do, and supports inheritance and abstract types, while still imposing discipline on mutating state. Why not? No-one ever said objects have to be mutable.

Don’t stray from the sweet spot.

As I have repeatedly stressed throughout the series, every language has their own ‘sweet’ spot or spots for the functional style; they will be larger and more numerous in some languages and smaller and fewer in others, and located in different places in each. Whichever language you are using, I recommend not trying to apply the functional style outside of its sweet spot. You will know when you have strayed too far when you find yourself having to undergo contortions in order to avoid mutating state, or in order to use functional programming constructs. Don’t do this just for the sake of it. Abandoning practicality and applying rules dogmatically is not pragmatic.

A couple of cases in point: Java lacks immutable collections. As a consequence, there is no practical way to create a collection by adding an element to an existing collection, for example as you could do in Clojure:

user=> (def v [1 2 3])

#'user/v

user=> (into v [4])

[1 2 3 4]

Sure, you can achieve this in Java without mutating state by concatenating streams and collecting the result to a list, but it’s really not worth it. It will make your code harder to understand and obscure its intent: exactly opposite to the principal benefit the functional style is supposed to bring. Just go with the flow of the language and mutate state locally:

<T> List<T> into(List<T> list, T value) {

var newList = new ArrayList<T>();

newList.addAll(list);

newList.add(value);

return newList;

}

Another thing Java lacks is literal collection initialisers. I would love to be able to create lists and maps in Java with the ease that I can in Kotlin or Groovy but alas, at the time of writing, we still cannot. You may be tempted to use streams in Java to get around this, but be pragmatic. This might seem like a good idea:

List<String> s = Stream.of("fee", "fi", "fo", "fum").collect(toList());

but don’t forget that you can always do this instead:

List<String> s = Arrays.asList("fee", "fi", "fo", "fum");

Streams are not the only game in town and often the mutable ways of doing things are the simplest. For example, you can do this to create a map, but please don’t:

Map<String, Integer> map = Stream.of(

new AbstractMap.SimpleEntry<>("one", 1),

new AbstractMap.SimpleEntry<>("two", 2))

.collect(Collectors.toMap(

AbstractMap.SimpleEntry::getKey,

AbstractMap.SimpleEntry::getValue));

because it is much simpler and far more natural to do this:

Map<String, Integer> map = new HashMap<>();

map.put("one", 1);

map.put("two", 2);

Remember that mutating state is not evil, or sinful, and that a program with no side effects would be useless. We don’t want to avoid all mutation of state, we just want to be disciplined about it. We want to know where our state is, how and when it gets mutated, and keep it encapsulated so that its effects are contained.

Don’t use higher-order functions for the sake of it.

This advice might seem strange given that I spent four whole episodes of this series explaining what you can do with first-class and higher-order functions, but I really mean it. If you can write your code in a more straightforward manner without using higher-order functions than you can with them, choose not to use them. First-class and higher-order functions add complexity to your programs, which is a cost, so make sure that they are giving you a payoff that leaves you in profit. Use them to make your code better, not just more ‘functional.’ Functional programming is a means, not an end. All other things being equal, the cleanest code should always win; if it happens to be imperative code, so be it.

These are not the abstractions you are looking for.

If we agree that it is possible to program in the functional style in an object-oriented language, it follows then that it makes no sense to throw away the benefits that OO programming give us. Most importantly, I mean here the ease with which we can create types that speak in terms of the problem domain. Functional programming promotes abstraction too, but I have observed that programmers steeped in FP tend to create types that are more algorithmic in nature, rather than talking in domain language. I wouldn’t say that you should avoid creating algorithmic abstractions, but I do urge you not to pass over the opportunity to write domain-specific code. Types that talk in terms of the problem the program is intended to solve - the ‘what’ - will be of greater aid to the programmers who need to understand your code after you are gone than types that speak in terms of how the problem is being solved. And remember that later programmer might be your future self!

Remember also that, whether programming in an OO style or a functional style or both, abstraction is a tool to be used, not an end in itself. Designs should be made more abstract when there is a purpose to it but the default, where there is no need for abstraction, should be always to write code that directly implements the requirements.

Functional code is more thread-safe.

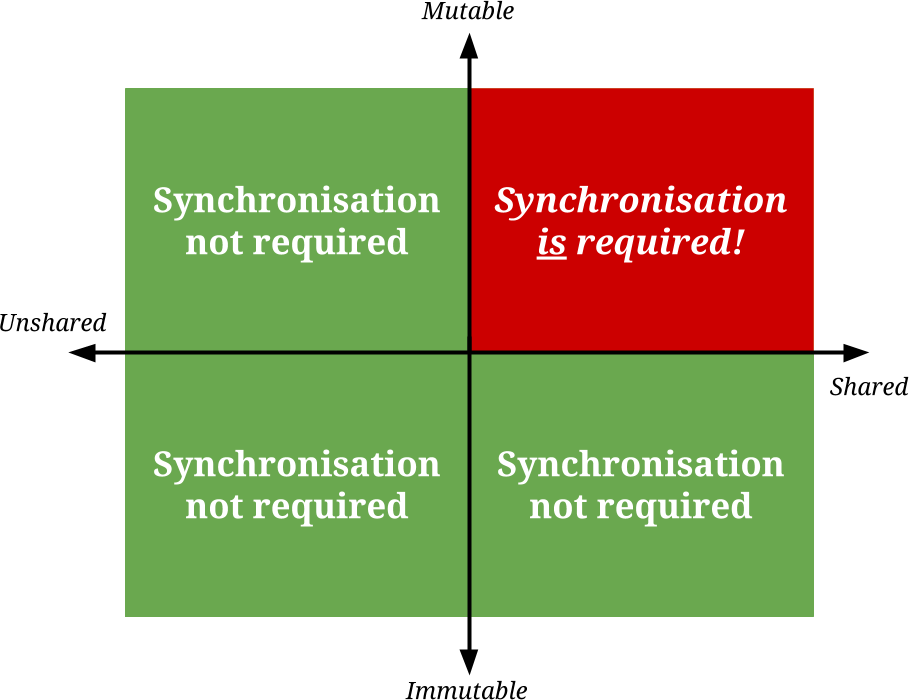

There is an additional motivation for adopting functional programming that we haven’t covered in the series, but is certainly worth mentioning. Maintaining discipline in mutating state also helps to avoid the pitfalls of concurrent programming. Kevlin Henney likes to illustrate this with a quadrant diagram like this one. It shows the four possible combinations of shared vs. unshared and mutable vs. immutable data:

In this diagram, only one quadrant is problematic, but programs tend to collect there as if it exerts some kind of gravitational field. The reasons are not mysterious. In the beginning, concurrent programming did not exist, because computer hardware and operating systems lacked support for concurrency. Consequently, all computer programs existed on the left “unshared” half of the diagram. Additionally, data was mutable because it was expedient to do so, due to resource constraints and computer architecture. So most programming occurred in the top-left “unshared and mutable” corner, and there it stayed for decades, until multiple cores started to become standard on consumer-grade hardware in the mid 00s, whereupon programming shifted right to the “shared and mutable” corner. That is where the pain is to be found.

When threads or processes share mutable data between themselves, synchronisation is required to prevent them from interfering with one another, which we often call “locking”. But locks are like gates in the program through which only one thread at a time can execute: they nullify the performance benefits of concurrency. The overhead associated with locking might even mean that a single-threaded program, requiring no locks, performs better than a multi-threaded program that uses locks, if there are too many locks or they are in places that critically affect the performance.

If your shared data is immutable, these synchronisation problems disappear in a puff of smoke. When data is not going to change, there is no problem with sharing it between threads. I’m not going to assert that this solves all the problems of concurrency, but it does drastically simplify things. In short, functional programming makes concurrent programming easier.

Favour clarity by default.

I was tempted to say that you should “favour simplicity” and, indeed, simplicity in programming is always what I strive for, but that is easier said than done. Simplicity is, ironically, anything but simple: I needed many years of experience to learn to see the simpler ways of doing things. I can tell this by looking at my old code and observing how overcomplicated it now seems to me. So although I do recommend favouring simplicity, I will not airily say to do so when I know it’s really hard to learn. Instead I will conclude by reminding of Donald Knuth’s oft-quoted warning, because I think it is particularly apposite to functional programming:

Premature optimisation is the root of all evil.

How does this relate to clarity? I mean that you should beware of abandoning the functional style for the sake of small efficiencies before you have measured and found it to be necessary. This is what Knuth meant by premature optimisation; it is the 97 percent of cases where no optimisation is really needed. In the absence of genuine performance and memory issues, it is better to tune your designs for expressiveness; in other words, write your code for readability by humans before you modify it for efficient execution by machines. In my opinion, the functional style done well results in more understandable code.

Also, question your assumptions about code efficiency: often it is seen that clear and simple algorithms outperform inscrutable ‘optimised’ ones anyway. The days of programming on the bare metal on machines with tiny memories are long gone and predicting exactly how the machine will behave when executing your program is non trivial. Today’s computing architectures are hugely complicated and many-layered: there is microcode, branch prediction and speculative execution, CPU caches, multiple cores, hypervisors, emulators, containers, operating systems, threads and processes, high-level languages and compilers, virtual runtimes, just-in-time compilation and interpreted languages, clusters and swarms, service-oriented architectures, serverless computing, and so on. Programming techniques have swung in and out of favour as computer systems have evolved; just as once upon a time people unrolled their loops for faster execution, then CPU caches made this practice counter-productive, but caches grew in size and the practice became efficient once again.

My point is that received wisdom oft outlives its applicability. So when making design choices in the name of efficiency, be sure that those choices are in fact valid. Test, measure and compare. In the absence of any observed performance issues, it is better not to optimise for efficiency at all.

Conclusion.

As Michael Feathers tweeted in 2010:

OO makes code understandable by encapsulating moving parts. FP makes code understandable by minimizing moving parts.

I think this is a nice way to understand it. By “moving parts” he clearly means mutating state, and notice that he says minimise not eliminate. When much state is in motion, it is far more difficult to predict how the machine’s global state will evolve while the program executes. This is a problem because a complete and accurate mental model of the execution is essential to write a program correctly. The functional style helps make this mental modelling easier, which can only be a good thing.

My main aim in writing this series has been to explain functional programming in terms that will be accessible to an experienced programmer, but without recourse to the arcane mathematical theories loved by some functional programming devotees. If the mathematics interests you, learn all about it and have fun. I am not opposed to it; I just don’t think it a prerequisite for adopting the functional style in your programs. In fact I find it completely orthogonal: I became convinced of the efficacy of functional programming before I had ever heard of category theory. Learning something of it afterwards did not increase or decrease my conviction at all. So I wanted here to try to make a case for functional programming that mirrored the way I came to appreciate it myself; to demonstrate through code examples that the functional style can be adopted, in a variety of programming languages, and that doing so brings benefits.

I hope this series has whetted your appetite and made you want to write your code more in this way. If it has, then my mission will have been a success.

Part 3 - First-Class Functions I: Lambda Functions & Map

Part 4 - First-Class Functions II: Filter, Reduce & More

Part 5 - Higher-Order Functions I: Function Composition and Monads

Part 6 - Higher-Order Functions II: Currying

Richard Wild

See other articles by Richard

WorksHub

Jobs

Locations

Articles

Ground Floor, Verse Building, 18 Brunswick Place, London, N1 6DZ

108 E 16th Street, New York, NY 10003

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join over 111,000 others and get access to exclusive content, job opportunities and more!